The inflation debate

Inflation has been a hot topic of debate amongst investors of late.

We all hope and expect there will be a strong economic recovery in the second half of 2021 as businesses and services re-open, perhaps driven by a successful vaccine roll out.

We are also seeing massive amounts of government and central bank stimulus and as a result, some people are concerned that all of this could be inflationary. If so, this could have a big impact on portfolios, where our target is to provide real returns well above inflation.

We recently held an internal debate on this topic, with different members of the investment team making the case for both high and low inflation outcomes. We like this approach to decision making as it really forces us to fully assess both sides of an argument and helps us avoid any unconscious bias.

We thought we’d share both sides of the debate as well as our conclusions and any relevant investment strategies we have included in portfolios.

Pent up demand – why the re-opening of the economy will cause an inflation spike, by James Carr

“How much did that just cost?”

“£18.”

“It’s a couple of coffees and a toastie!”

This is a paraphrased version of the conversation I recently had with my girlfriend Alex outside Starbucks as I waited with our dog Norman (more on him later!).

Starbucks has pricing power as the world’s largest coffee chain with a loyal customer base, allowing them to push through small price hikes without anyone really noticing. This got me thinking about the potential for huge supply and demand imbalances as the economy re-opens.

Dogs are a great example of where inflation is already happening. Already a nation of dog lovers, many households who previously could not fit a dog in to busy lives have found this much more practical when working from home!

There is only a limited supply of dogs at any one time and the huge surge of demand has led to astronomical price rises. Norman is a three-year-old Cockapoo that we bought for around £850 in 2018. Using the same website, the cheapest puppy currently available is over double the price with many as much as five times the price.

Many households have had the dual boost of being able to save more and pay off more debt and have huge pent-up demand to do the things that we all used to enjoy pre- pandemic, from eating out at restaurants to going on holidays.

The biggest driver of CPI in December in the UK was recreation, and this was in a month with partial lockdowns in place. When the economy is fully re-opened, this huge pent up demand alone could drive inflation up.

This example can be extended out to retail shopping. Following 12 months of shopping online, will consumers want to purchase goods in-person and while talking to someone who can assist them, rather than stick with the cold efficiency of Amazon Prime?

More in person shopping could lead to reduced discounting and higher prices as, at present, many high street stores are forced to slash prices and margins to compete with the efficient online only offerings.

Lower for longer – why inflation is not a problem, by Neal Foundly

Yes, there will be a pick-up in prices caused by the pandemic dislocation but this will be benign and short- term.

We can all understand that goods and people are not where they should be and it is reasonable for companies to pass on some of the extra costs to supply them.

Inflation will temporarily be pushed higher, but this will quickly pass.

Some forecasters think that this is a portent for a more enduring, longer-lasting spell of higher inflation. Why? Well, many expect the huge amounts of monetary and fiscal stimulus to be a big driver.

As we all know, central banks have been pumping money into the economy by buying bonds since the Credit Crisis. They stepped up the pace of this quantitative easing significantly last year once the pandemic struck. The theory says that all this money has got to be spent on the same amount of goods and services and so prices will go up as demand exceeds supply.

What this does not take into account is that for inflation to rise, the cash needs to be spent and, quite simply, this has not been the case. In fact, the pace of spending has been falling significantly.

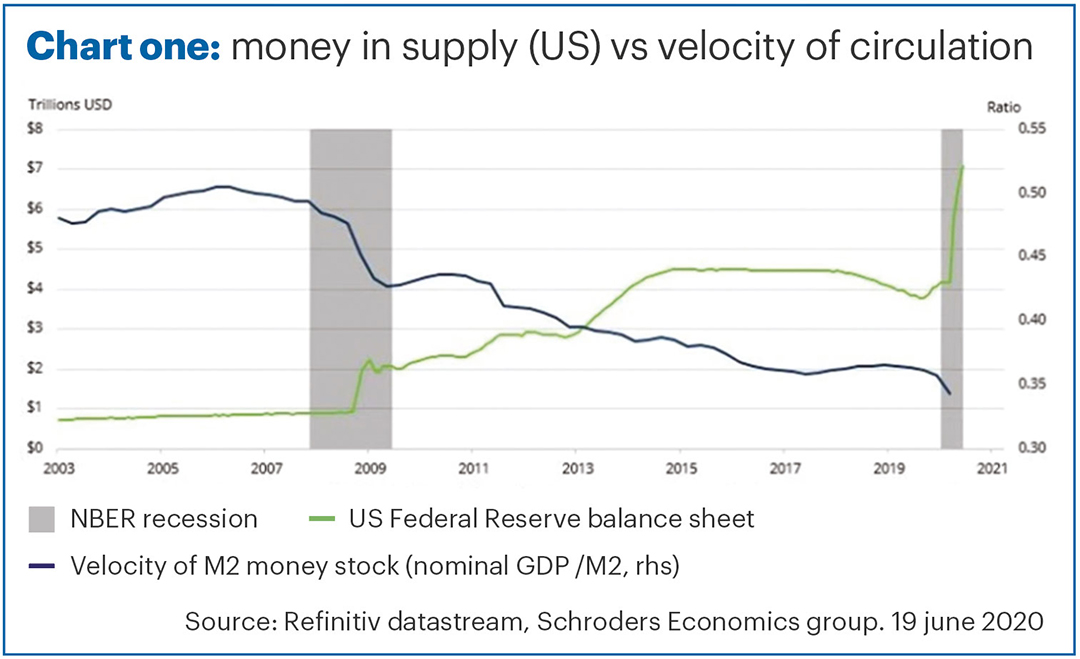

Chart one shows how sharply the money supply in the US (green line) has gone up in recent years. However, at the same time as the “velocity of circulation” (blue line) has correspondingly fallen, which is why this hasn’t been inflationary.

At the end of the day, all major central banks have a mandate to keep inflation at around 2% and all have failed in the last decade, consistently undershooting the target.

If it was as easy as printing money (which is one thing they can control) you have to ask yourself, why haven’t they hit their targets?

James Carr – why printing money could cause inflation

Chart one can be used as both a bull and bear case for inflation!

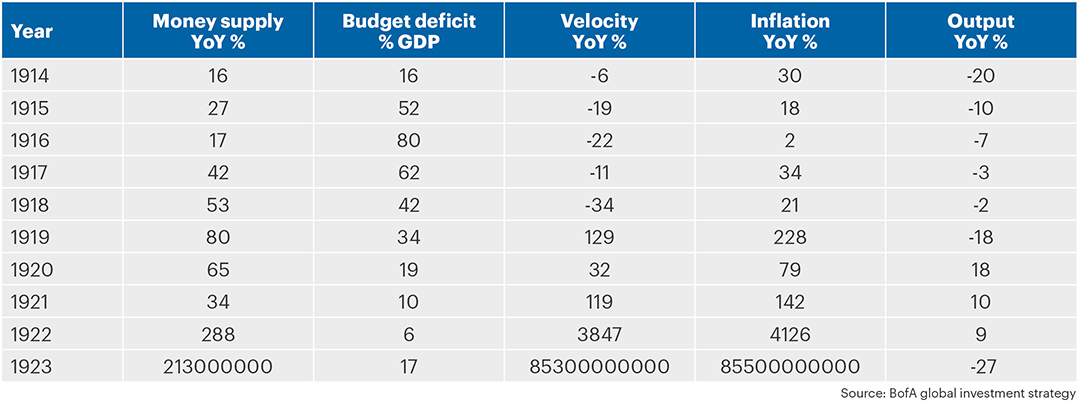

Simply printing money might not be inflationary, however more money chasing the same finite supply of goods and services can be. We can use an extreme example and contrast this back to World War I in Germany, when the velocity of money slowed down over a multi-year period.

Table one shows that this lower velocity failed to keep inflation low. As we know there was huge inflation spike in the years following the war, and in fact the velocity of money increased when the war ended.

And what about all the government spending last year and for the next few years to get the economy back onto its feet, surely that’s going to push up prices?

Neal Foundly – no link between government spending and inflation

Well, let’s look at the evidence. Researchers have found there is very little linkage between the growth in government spending and inflation.

The Federal Board of St Louis looked at the historical evidence in the US and declared, “we found no effect of government spending on inflation”.

Indeed, when reviewing the potential effect on inflation by President Biden’s proposed new stimulus package for this year, amounting to 10% of GDP, the chief economist at the IMF said it was “nothing to be concerned about”.

James Carr – commodity prices will be inflationary

There are further indicators that inflation could be hiding in plain sight. Commodity prices are a driver of inflation, and in 2020 we had all the components that make up the main commodity index rise at the same time. This has never happened in the previous 50 years and was in a year of falling inflation globally.

There are also softer factors at play that can be hard to quantify; we are in the early stages of the Brexit transition and the fuel on the demand fire could be post-Brexit red tape surrounding supply chains forcing companies to bring manufacturing back to the UK and not being able to cheaply outsource to the rest of the world.

Neal Foundly – no sign of a commodity supercycle

Again, these might be short-term drivers but short term is not an issue. For long-term inflation we need to see another “supercycle” in commodities.

The supercyle theory says that commodity prices rise and fall in multi-year cycles and we are due another upcycle.

The problem with this is, why? I can explain the previous cycles – the end of World War II, the industrialisation of the US and, most recently, China joining the World Trade Organisation in 2001 adding 1.4 billion consumers to demand – but where is the global-scale shift in demand coming from to drive prices higher this time?

The fact is, there is significant underutilised capacity in the world and with global supply chains from low-cost countries, prices are constantly kept in check. One of the most important drivers has been the move by workers in developed countries to accept lower wages which gives them more of a chance to compete with cheaper overseas labour and a chance to stay in a job.

With wage costs restraint, the additional debts from the pandemic to pay for and the on-going deflationary forces from new technologies, inflation may hit the headlines over the next month or so but don’t be fooled by the siren call of higher prices.

Mike Deverell – A balanced view

We’re not called Equilibrium for nothing!

We don’t tend to take extreme positions or big bets in portfolios. We weigh up the evidence and may make small adjustments to the positions in line with our views, always mindful of what happens if we’re wrong.

In true Equilibrium style, we think both sides of the argument have merit! In essence, we expect inflation to spike higher in the short term but remain low in the long term.

Inflation is always quoted as a year-on-year number. The latest figure we have for the UK Consumer Prices index (CPI) is from January when inflation was 0.7% pa, well below the 2% target.

The low point during the pandemic was in August 2020 when CPI was just 0.2%, meaning that prices were only just higher than they had been in August 2019.

This was partially the result of the ”Eat-Out-to-Help- Out” scheme and temporary VAT cuts in the hospitality industry, pushing down prices. If there is no similar scheme this August and when those VAT cuts are eventually reversed, this will be inflationary. Prices this August could be much higher than the previous August, simply because the prices in 2020 were so low.

We call these “base effects” and they are important drivers of short-term inflation. It is also not anything to be concerned about in our view as it is temporary.

There may well be short-term supply and demand imbalances when the economy re-opens. However, this will likely only last a few months. There is still plenty of “slack” in the economy, with high levels of unemployment and an estimated four million people currently furloughed.

When government support comes to an end, some of those furloughed people could lose their jobs permanently.

The biggest driver of long-term inflationary trends is long-term economic growth. In turn, this is driven largely by demographics.

Economic growth comes from output increasing compared to the previous year. We will only increase output if we become more productive (each worker produces more) or the number of workers increases.

With the number of working age people as a percentage of the population predicted to decline over the long term, we think long-term economic growth (once recovered from the pandemic) will likely remain low and so will inflation.

But what if we’re wrong? Well, the good news is we have plenty of natural inflation protection in our portfolios.

Equities tend to provide protection, particularly if we invest in companies which can pass on price rises to consumers, meaning increased revenues and profit margins which remain stable.

We also have assets like infrastructure and property in portfolios, where the income they receive goes up in line with prices.

Whilst we don’t believe inflation is much of a threat to portfolio returns, even low levels of inflation are a threat to cash savings. We don’t expect rates to go up any time soon, so, in real terms, we’d expect most cash accounts to be losing money.