Misleading statements

Discussing the Chancellor’s spending review back in November 2020, the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg tried to give some context around his tax and spending decisions:

“There is no money left,” she said. “This is the credit card, the national mortgage, absolutely everything maxed out”.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t truly reflect how government finances actually work and at the time, prompted a group of leading economists to write to the BBC to complain.

Government finances work in a very different way to a household, or even a business. Of course, this can be complicated and so naturally the media use analogies as a way to simplify the jargon.

But phrases like “maxing out the credit card” can be misleading as it brings to mind extremely high levels of interest and feelings of panic that the government is about to go bust.

The mortgage analogy implies borrowing against an asset. Our government has all sorts of assets, both physical and financial, not least the ability to raise future taxes.

However, even this analogy can be problematic. Mortgages have fixed repayment dates. Even if we have the option of re-mortgaging, most of us would like to pay our mortgage off before we retire. But the government never retires, so there is no set date at which we need to pay off our national debt.

Similarly, the secure income stream from taxation for the government is very different from the risk of loss of earnings for an individual.

In meetings, our clients often express concerns about the level of government debt and about the legacy we are leaving for our children. This is an important issue and often an emotive one.

However, without a better public understanding of government finances, it is difficult to have an informed debate. This blog aims to define some of the commonly used terms and discuss some of the popular misconceptions.

Debt or deficit?

The terms ‘debt’ and ‘deficit’ can often be confused – they are two very different things but are often mistakably used as interchangeable terms.

Deficit: when we talk about deficit in this context we mean the ‘fiscal deficit’ (not to be confused with the ‘trade deficit’ – when an economy imports more than it exports). Put simply, this is the difference between tax and spending, or rather the government’s incomings and outgoings.

A deficit sounds like a terrible thing. If we relate it to our personal finances, should we have a constant deficit (we spend more than we make) then it won’t take long before we’re bankrupt.

However, governments are different. In fact, they are rarely in surplus.

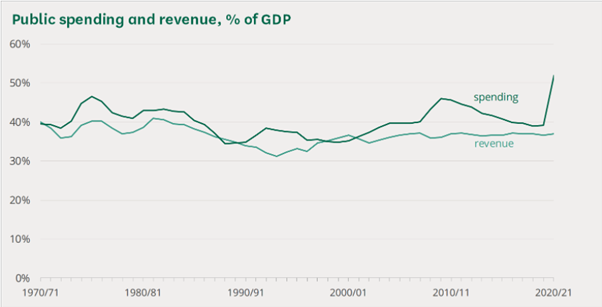

Chart one (below) shows the UK’s public spending and revenue over the past fifty years. Only twice during this period has revenue (briefly) exceeded spending.

Source: parliament.uk “The budget deficit, a short guide” 14.12.21

The fact is, governments can (in theory) run a deficit forever. To explain why, we need to look at how debt works.

Debt: the total amount that the government owes.

We normally look at debt relative to the size of our economy, which we call the debt to GDP ratio. GDP means gross domestic product – the total annual output of the UK economy.

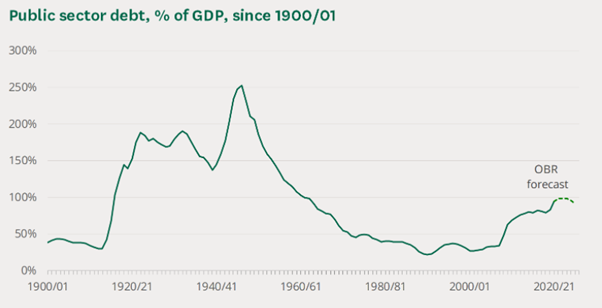

Chart two (below) shows how our debt to GDP ratio has changed over time. The current level of 94% is the highest since the 1970s, although it has been much higher at times in the past:

Source: parliament.uk “The budget deficit, a short guide” 14.12.21

When we say the debt to GDP ratio is 94%, this means the total government debt is equivalent to 94% of one year’s output for the UK economy as a whole.

It’s all relative

By running a deficit all the time, the size of our debt is naturally increasing. However, if we were to increase our economic output (GDP) quicker than we increase the size of our debt, our debt to GDP ratio would actually go down.

Running a higher or lower deficit makes more sense at different times in the economic cycle. When the economy is in recession, we actively want the government to increase the deficit to boost growth.

For example, if the government borrows money to spend on infrastructure (for example), this provides income to construction companies (who pay taxes on their profits), who in turn employ workers (who pay taxes on their wages).

Those workers then spend much of their wages on goods and services (often paying Value Added Tax). The companies who they purchase those goods or services from also pay tax, employ workers (who pay tax), and then THOSE workers go out and spend…and so on and so forth. This is called the ‘multiplier effect.’

Of course, some spending is more ‘productive’ than others with a greater or lesser multiplier. Investment spending that produces a return higher than the cost of borrowing the money is often a sensible thing to do.

However, there is a tipping point when borrowing becomes too high. To discuss where that level is, we need to look at who the government owes money to and how much interest it has to pay on that debt.

Gilt-y as charged

So, who does the government owe money to?

Answer: You.

If you’re an investor with Equilibrium you will own (indirectly at least), UK government bonds known as gilts. Gilts are the main form of UK government borrowing.

When we buy gilts this essentially means we’ve lent money to the UK government and in return they pay us some interest. Gilts are a very safe investment since they are guaranteed by the government so only tend to provide a very low yield.

The yield is essentially set by supply and demand. The greater the appetite from investors, the less the government has to pay in interest.

Around 1/3rd of gilts are held by insurance companies and pension funds (according to the Financial Times (FT) using data from end of September 2020). These directly or indirectly fund pension payments and act as security against their liabilities.

Another 1/3rd is owned by overseas investors and institutions.

Meanwhile, around another 1/3rd is owned by the Bank of England as part of quantitative easing (also known as QE, which I will come to in a minute).

As of 29 December 2021, the government pays interest of around 0.5% p.a. on 1-year borrowing, less than 1% on 10-year gilts and just 1.1% on 30-year debt (Source: Refinitiv Datastream).

One of the most important measurements in government finance is actually one of the least discussed, certainly in the mainstream media. That is the total interest cost – in other words how affordable the debt is.

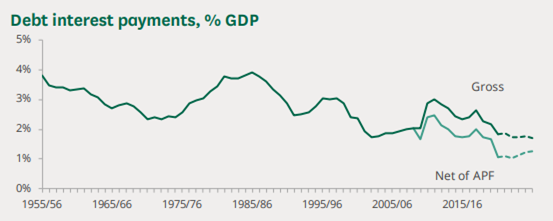

Chart three (below) shows the debt interest as a percentage of GDP and how this has changed since the 1950s.

Source: parliament.uk “Government borrowing, debt and debt interest” 27.05.21

You may be surprised to learn that the government’s net debt interest cost as a percentage of GDP has never been lower!

Printing money

Taking into account the effect of the Asset Purchase Facility (APF) – the bonds owned by the Bank of England – the interest the government pays on its debts amounts to just 1% of GDP.

We will discuss QE and monetary policy in more detail in another blog but, put simply, QE involves the Bank of England electronically ‘printing’ money and then using this to buy gilts.

By buying gilts, this pushes up their price which in turn pushes down the yield. QE indirectly reduces borrowing costs by increasing the demand for, and reducing the supply of, gilts.

However, there is a more direct effect. When the Bank of England holds gilts, interest is paid on them by the Treasury. Whilst it is operationally independent, the Bank is owned by the government. Essentially, this is one branch of the State paying interest to another.

Frankly, this makes no sense and so the Bank therefore repays the interest it receives on its gilts back to the Treasury again. Given that it owns around 1/3rd of all gilts, this effectively means the interest cost of 1/3rd of our government debt is (in practical terms) zero.

Magic money tree

Countries who have their own currencies such as the UK, the US or Japan (but not countries like Greece who are part of the Euro), have a great deal of freedom around their government finances.

In essence, their central banks can magically create money out of nowhere. The UK government will ALWAYS be able to repay its debt since it can order the Bank of England to print the money to pay for it.

Saying that, this is not the same as a magic money tree. Investors need confidence that a government will be sensible with its finances. Money is ultimately a confidence trick – it has no intrinsic value. The pound’s only value comes from the confidence that we can use it to exchange for goods and services, and the knowledge that the government can ask for payment of that currency in the form of taxes.

If governments are careless with that trust and ‘print’ too much money, this would lead to inflation. The pound’s value relative to other currencies will drop and investors will be less willing to lend us money.

It is therefore important that government debt is used sensibly. People of different political persuasions will likely have differing views as to where is an appropriate level.

However, it is important to understand some of the basics around government finances if we are to make informed decisions about who to trust to look after them.

This blog is intended as an informative piece and does not construe advice. If you have any further questions, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with us using the form below or by reaching out to your usual Equilibrium contact.